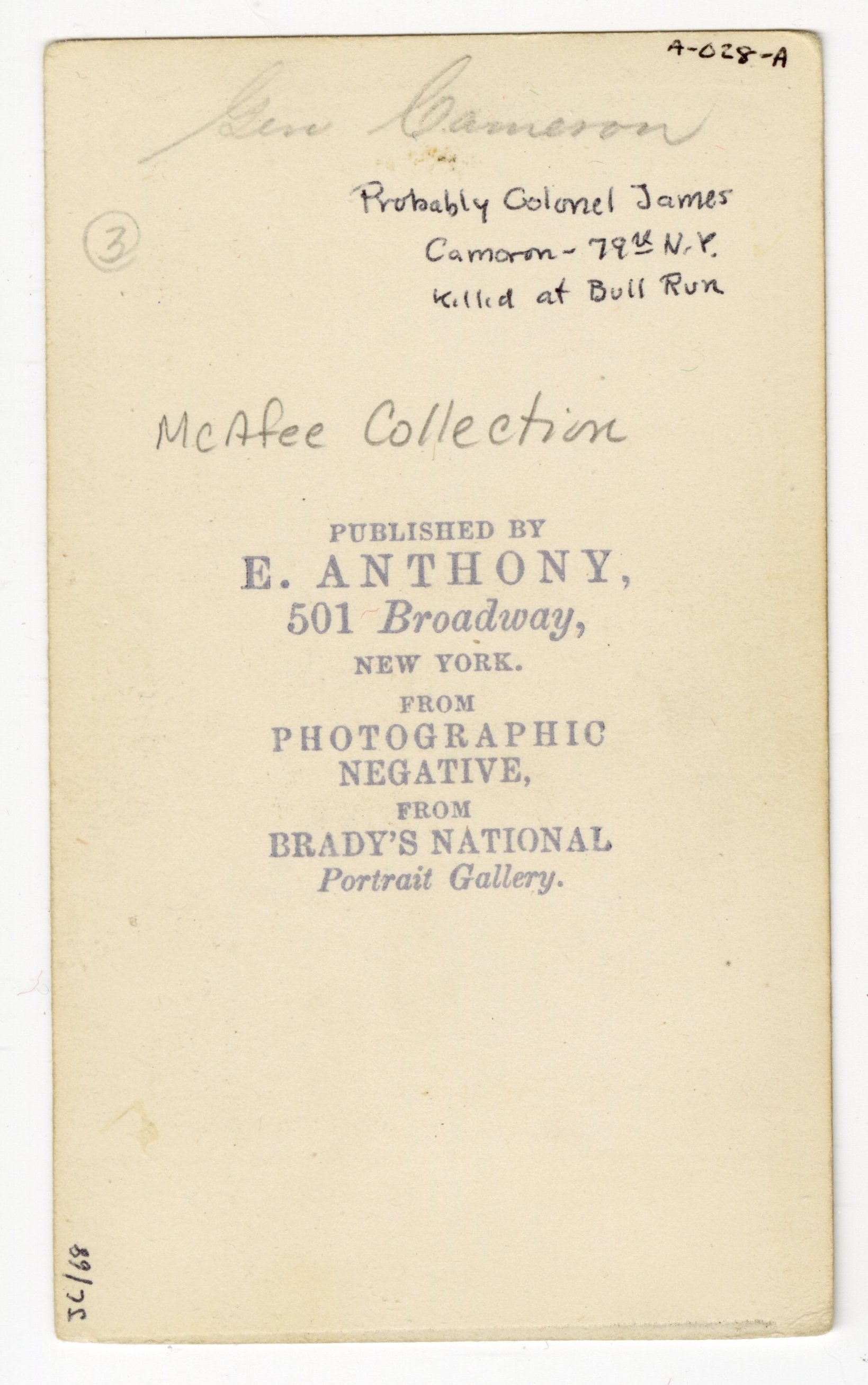

79th New York Infantry - Highlanders - Killed at 1st Manassas

Item CDV-10900

James C. Cameron

Price: $585.00

Description

James Cameron (March 1, 1800 – July 21, 1861) was a Pennsylvanian who served as colonel of the 79th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment of the Union Army during the early days of the American Civil War (Civil War). He was the brother of Simon Cameron, United States Senator and first United States Secretary of War in the cabinet of President Abraham Lincoln. At the age of 61, James Cameron was killed in action at the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large battle of the war, on July 21, 1861.At the outset of the Civil War, James Cameron decided to serve as a matter of duty and he proceeded to Washington, D.C. The 79th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, known as the "Highlanders" because its initial core militia companies were composed mostly of Scotsmen or men of Scottish descent, was one of the earlier units to arrive in Washington, D.C., after President Lincoln called for troops to suppress the rebellion. Having arrived under the command of its lieutenant colonel, the 79th offered the position of colonel to James Cameron, a prominent man of Scottish descent and brother of Simon Cameron, the Secretary of War. At least two sources suggest that Simon Cameron's influence played a part in the selection. James Cameron accepted the position of colonel of the regiment on June 20, 1861. By the time the regiment had filled its ranks, a majority of the men were not of Scottish background and in fact, many were of Irish heritage.

On July 7, 1861, the 79th New York Infantry moved to Virginia as Major General Irvin McDowell began the advance of the Union Army that would lead to the First Battle of Bull Run. The regiment was in the division of Brigadier General Daniel Tyler and the brigade of Colonel William T. Sherman. On July 18, 1861, Tyler's division and the 79th New York Infantry participated in a reconnaissance in force in which the regiment came under fire and where the Union force was unable to penetrate the Confederate line at the Battle of Blackburn's Ford.

One account of the 79th New York Infantry going into battle on Henry House Hill, where Confederate forces had started to rally, at a critical point in the First Battle of Bull Run states that Colonel Cameron was on the right side of the regiment's line and shouted "Come on, my brave Highlanders" as the line advanced. Other sources say he shouted: "Scots, follow me." A private in the 79th New York Infantry, William Todd, wrote that as the regiment was half way up the hill, they were hit by a volley from the Confederates that staggered them. At this point, with reference to Cameron, Confederate Colonel, later Lieutenant General, Wade Hampton III reportedly said: "Isn't terrible to see that brave officer trying to lead his men forward and they won't follow him." Cameron continued to inspire his men with his bravery in leading charges in an effort to recover Union batteries lost on Henry House Hill. Reforming at the direction of their officers after having been first repulsed, the regiment proceeded only to be hit by another volley that killed Colonel Cameron and inflicted additional casualties. Cameron was talking with a lieutenant from Company J of the regiment when a bullet hit him in the chest. He collapsed and died of massive bleeding in a matter of moments. The body was taken to an ambulance wagon, but the driver protested that it was needed for the wounded. After being told of the dead man's identity, the driver relented and allowed it to be placed there. However, the ambulance wagons were quickly captured by the Confederates, who then commandeered them for their own wounded. Thus, Colonel James Cameron, brother of U.S. Secretary of War Simon Cameron, was killed during the first major battle of the Civil War, the First Battle of Bull Run. Simon Cameron had been among the crowd of spectators who came out from Washington, D.C., to witness the battle.

From the earliest reports after the battle, a story emerged that Wade Hampton himself had targeted officers of the 79th New York Infantry, mistaking it for the 69th New York Infantry, one of whom had killed his nephew early in the battle, and that Hampton killed Colonel Cameron with his second or a later shot at him. At least two sources note the similarity between Cameron's death and the death of Lieutenant Colonel Philips Cameron of the regiment's namesake regiment, the 79th Regiment of Foot (Cameron Highlanders) by being shot by the colonel of a French regiment at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on May 5, 1811, during the Napoleonic Wars.

Following Colonel Cameron's death, after some hesitancy about firing on men who might be part of the Union force, the 79th New York Infantry was hit with another volley which caused the remaining men in the decimated force to retreat. The 79th New York Infantry "Highlanders" had sustained casualties of 32 killed, 51 wounded and 115 missing. Hampton's Legion and the 5th Virginia Infantry fought off attacks by four Union regiments, including the 79th New York Infantry, within forty minutes. Confederate Colonel Wade Hampton sustained slight head and ankle wounds during the charge of the 79th New York Infantry and while lying near the Henry House, tried to direct his men through messages carried by staff officers. Hampton's stand allowed Stonewall Jackson's brigade to have enough time to reach that critical spot on the battlefield.

Cameron's body was thus left on the field. Attempts to retrieve it from the Confederate lines under a flag of truce were unsuccessful; a letter addressed to Confederate army headquarters asking for its return was rejected due to objections over the wording of the letter; it was addressed "To whom it may concern." and the Confederate authorities replied back that the retrieval of Cameron's body was not a matter that concerned them, and they would not accept unless the letter was properly addressed. The body was not retrieved until the Confederate army withdrew from the Manassas area in March 1862. A party led by Cameron's adjutant at the battle, Sgt. John Kane, found a slave who had helped bury the dead on the battlefield. He testified that Cameron's body had lain unburied in the hot summer weather for a few days prior to being placed in a common grave with other Union dead, and that he had made a mental note of where it was buried after hearing that a reward was being offered for its recovery. Upon digging in the spot that the slave had pointed out, they found Cameron along with the remains of several enlisted men. The body was identified by its clothing and a hernia truss that the colonel had been wearing. Cameron's personal effects and $80 in cash he had been carrying were missing; the slave said that Confederate cavalrymen had looted of the body of anything valuable. After carefully removing Cameron's remains, they were taken back to Washington and eventually interred in the Lewisburg Cemetery in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

Source: Wikipedia